The Comic Strip That Spoke Volumes: How Do Authors Master Concise Writing?

How four yellow panels in 1896 proved that brevity isn't about cutting words—it's about choosing the right ones

Definition

Concise writing means expressing complete ideas using only necessary words—eliminating everything that doesn't serve clarity or impact. It's not about writing less; it's about wasting nothing. Every word must earn its place by either advancing meaning, creating emotion, or building rhythm. Brevity without substance is empty; substance without brevity is exhausting.

Analogy Quote

"The sharpest blade has no excess metal." — CL Witt

Historical Story

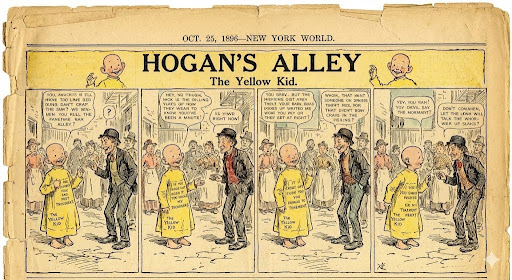

On February 16, 1896, Richard F. Outcault's "The Yellow Kid" appeared in Joseph Pulitzer's New York World newspaper—and changed storytelling forever.

The strip featured a bald, gap-toothed child in a bright yellow nightshirt navigating the chaos of immigrant tenement life. But here's what made it revolutionary: Outcault had to tell complete stories in four panels.

No room for exposition. No space for elaborate descriptions. Every image, every line of dialogue, every facial expression had to carry maximum weight. If a word didn't advance the story, it disappeared.

Previous newspaper illustrations were elaborate—dense with text, cluttered with explanation. Outcault did the opposite. He understood that readers scanning a crowded newspaper page would only stop if something grabbed them immediately.

So he stripped everything to essentials. Four panels. One joke. Zero wasted space.

The Yellow Kid became an instant sensation. Not because it was sophisticated—but because it was efficient. Readers could absorb a complete narrative in seconds. The constraint of limited space forced Outcault to become a master of compression.

Other cartoonists noticed. Within months, comic strips exploded across American newspapers. Each one proved the same principle: the less room you have, the more disciplined you must be about what you include.

Outcault didn't invent visual storytelling. He perfected the art of saying everything by eliminating anything that didn't matter.

The panels taught him what every writer eventually learns: constraints don't limit expression—they clarify it.

Our Connection

Every writer starts by overwriting. We explain too much, describe too thoroughly, include every thought that crosses our minds. We're terrified readers won't understand unless we spell out every detail. But just as Outcault discovered that four panels communicated more than elaborate illustrations, writers discover that tight prose hits harder than verbose explanation. The reader's imagination is more powerful than your description. The question isn't "How much can I fit in?"—it's "How much can I trust my reader to infer?"

Modern Explanation

Concise writing isn't about word count—it's about word value.

A 500-word article can feel bloated if 300 words are filler. A 5,000-word essay can feel lean if every sentence delivers new insight. The goal isn't brevity for its own sake; it's maximum meaning per word.

Outcault mastered this through constraint. Four panels meant he couldn't waste a single image on setup that didn't pay off. Modern writers face similar constraints: readers scrolling social media, skimming emails, deciding in seconds whether to keep reading.

The writers who succeed understand three principles:

Precision beats decoration. Ornate language might feel literary, but if it doesn't serve the point, it's self-indulgence. Choose the exact word instead of the impressive one.

Trust creates speed. When you trust readers to make connections, you can skip obvious transitions and explanations. Comic strips work because they trust you to fill gaps between panels. Writing works when it trusts readers the same way.

Constraint reveals essence. If you had only 100 words to explain your idea, what would you keep? That's usually what mattered all along.

The irony: tight writing takes longer to produce than loose writing. Editing for concision requires ruthless honesty about what actually serves your reader versus what makes you feel clever.

Outcault spent hours on four panels. Bad cartoonists would have filled eight panels with the same joke.

Great writers say more by saying less—not because they lack ideas, but because they respect their readers' time.

The Comic Strip Framework

The Comic Strip Framework teaches that concision isn't about cutting—it's about choosing. Every element you include must justify its existence.

Contrarian Insight

Most writers believe concise writing means deleting adjectives and shortening sentences.

The truth: concision means deleting ideas that don't belong.

Trimming words from bloated sentences is cosmetic. Real concision happens when you ask: "Does this entire paragraph need to exist? Does this chapter serve the book? Does this subplot advance the theme?"

Writers protect weak sections by editing them instead of cutting them. We think, "If I just polish this passage, it'll work." But polishing a unnecessary paragraph is like perfecting a comic panel that doesn't advance the joke—it's still wasting space.

Outcault didn't make weak panels better. He eliminated them.

The hardest part of concise writing isn't the cutting—it's admitting that the material you labored over doesn't serve your reader. You might love that description, that tangent, that clever aside. But if it doesn't earn its place by advancing meaning or emotion, it's clutter.

The paradox: writers who can kill their darlings produce work readers actually finish. Writers who protect every sentence produce books readers abandon.

Concision isn't cruelty to your writing—it's respect for your reader.

Action Steps

Here's how to apply the Comic Strip Framework and master concise writing:

Identify your punch. Before writing anything, finish this sentence: "The one thing my reader must understand is ___." Everything else is supporting structure.

Use the 50% test. After your first draft, cut half. Not half the words—half the content. Which paragraphs could disappear without losing essential meaning? Delete them.

Hunt for empty phrases. Search your draft for: "in order to" (use "to"), "due to the fact that" (use "because"), "at this point in time" (use "now"). Replace filler with precision.

Trust your reader's intelligence. If readers can infer it from context, don't explain it. Comic strips work in the gaps—so should your writing.

Read aloud with impatience. Pretend you're bored and scanning. Which sentences make you want to skip? Those need cutting or tightening.

Apply the panel test. If your piece were limited to four key sections, what would you keep? Why are you including anything else?

Choose concrete over abstract. "He was angry" tells. "He slammed the door" shows. Specific images compress more meaning than vague descriptions.

Eliminate permission phrases. Delete: "I think," "in my opinion," "it seems to me." Your readers know it's your opinion—you wrote it.

FAQs

Q1: How do authors master concise writing?

A1: By eliminating everything that doesn't serve clarity or impact. Concision means choosing necessary words, trusting reader intelligence, and deleting ideas that don't advance meaning—not just trimming sentences.

Q2: Is concise writing the same as short writing?

A2: No. Concise means efficient—maximum meaning per word. A 5,000-word essay can be concise if every word earns its place. A 500-word article can be bloated if filled with filler.

Q3: How do I know what to cut?

A3: Ask: "If I removed this, would my core message change?" If the answer is no, cut it. Protect ideas that matter; delete decoration that doesn't.

Q4: Won't cutting too much make my writing feel choppy?

A4: Only if you cut rhythm and flow. Concision removes waste, not grace. Read aloud—if it sounds stilted, you've cut muscle instead of fat.

Q5: How much should I cut in revision?

A5: First drafts are often 30-50% longer than they need to be. Expect to cut substantially. If cutting feels easy, you're removing obvious bloat. If it feels painful, you're making necessary choices.

Q6: Can creative writing be concise?

A6: Absolutely. Hemingway, Carver, and Atwood prove that literary depth doesn't require verbosity. Poetic compression often creates more emotional impact than elaborate description.

Q7: What's the biggest enemy of concise writing?

A7: Fear that readers won't understand. We over-explain, repeat unnecessarily, and hedge our statements. Trust is the foundation of concision.

Q8: How long should it take to edit for concision?

A8: Plan to spend as much time cutting as you did writing. Outcault spent hours perfecting four panels. Quality compression requires deliberate effort.

Call to Action

"Say more by wasting less. Master concise writing at BeyondTheBind.com/FreeTraining."

Sources

Library of Congress – The Yellow Kid and the Birth of Comics

Smithsonian Magazine – How Comic Strips Changed American Storytelling

Author: Curtiss Witt | Zzyzxx Media Group AI

Edition – Updated January 11, 2026