The Dream That Served a Movement: How Do Authors Write to Change Lives, Not Chase Fame?

How Martin Luther King Jr.'s 1963 speech proved that lasting impact comes from service, not performance—and why the most powerful writing solves problems readers didn't know they could name

Definition

Writing as service means creating work that genuinely helps readers solve problems, clarify confusion, or navigate challenges—rather than showcasing your talent or building your brand. Service-driven writing asks "What does my reader need?" instead of "How do I look?" It prioritizes transformation over applause, utility over vanity, and reader outcomes over author recognition.

Analogy Quote

"The words that change the world are the ones that served it first." — CL Witt

Historical Story

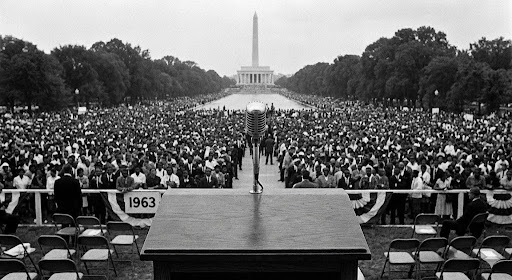

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. stood before 250,000 people at the Lincoln Memorial and delivered what would become the most quoted speech in American history.

But here's what most people don't know: the "I Have a Dream" section wasn't in his prepared remarks.

King had written a speech about economic injustice, legal barriers, and the urgency of the civil rights movement. Solid. Necessary. Important. But midway through his delivery, gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, standing nearby, called out: "Tell them about the dream, Martin! Tell them about the dream!"

King paused. Then he set aside his written text and spoke from the heart.

What followed wasn't performance—it was service.

He didn't talk about his rhetorical skills or his leadership credentials. He didn't try to sound brilliant or original. Instead, he painted a picture of a future where his listeners' children could live free from discrimination. He named their pain, validated their exhaustion, and offered them vision when despair felt overwhelming.

Every sentence served the audience's need for hope, clarity, and direction.

The prepared speech would have been forgotten. The improvised dream became immortal—not because it was eloquent, but because it was useful. It gave people language for their longing. It translated rage into resilience. It turned individual suffering into collective purpose.

King understood what most writers forget: your audience doesn't need you to be impressive—they need you to be helpful.

The speech worked because King focused entirely on what his listeners needed to hear, not what he wanted to say. That's the difference between performance and service.

Performance asks: "How do I sound?"

Service asks: "What do they need?"

One builds ego. The other builds movements.

Our Connection

Every author faces the same choice King faced: write to look good, or write to do good. Performance-driven writing chases awards, impressive prose, viral moments, and industry recognition. Service-driven writing chases reader transformation—solving actual problems, answering real questions, offering clarity when confusion reigns. The cruel irony: writers who chase performance rarely achieve lasting impact, while writers who focus on service often receive recognition as a byproduct. King didn't set out to deliver history's most memorable speech. He set out to give hurting people hope. The memorability came because the service was real.

Modern Explanation

Writing as service requires a fundamental shift in perspective: from author-centered to reader-centered creation.

Performance writing asks:

Does this make me sound smart?

Will this impress agents or critics?

Is this unique enough to stand out?

Does this showcase my voice?

Service writing asks:

Does this solve a problem my reader has?

Will this make their life easier, clearer, or better?

Have I answered the question they're actually asking?

Does this respect their time and intelligence?

The difference shows up everywhere. Performance-driven blog posts use elaborate vocabulary to signal intelligence. Service-driven posts use simple language to ensure understanding. Performance-driven novels prioritize stylistic innovation over emotional resonance. Service-driven novels prioritize reader experience over author experimentation.

This doesn't mean dumbing down or pandering. King's speech was intellectually sophisticated—but its sophistication served clarity, not vanity. He used repetition ("I have a dream") not to show off rhetorical skill, but to burn the vision into memory.

Service writing is harder than performance writing because it requires:

Deep empathy (understanding what readers struggle with)

Humility (accepting that it's not about you)

Discipline (cutting anything that serves ego instead of reader)

But service writing lasts. Performance writing impresses momentarily, then disappears. Service writing transforms lives—and that transformation creates loyalty, word-of-mouth, and legacy.

King's speech didn't trend for a week. It's been quoted for sixty years.

The MLK Framework

The MLK Framework teaches that great writing doesn't announce itself—it disappears into the reader's transformation. They remember how you helped them, not how clever you sounded.

Contrarian Insight

Most writers believe success means building a personal brand, cultivating a distinctive voice, and making their name recognizable.

The truth: the most successful writers are the ones readers can't imagine living without.

Brand obsession is performance thinking. You're trying to be memorable, quotable, impressive. But readers don't care about your brand—they care about their problems.

King became an icon not by building a personal brand, but by serving a movement. His name became inseparable from civil rights because he subordinated his ego to the cause. He didn't ask "How do I become famous?" He asked "How do I help my people?"

Writers make the same mistake across every genre:

Novelists prioritize "literary" prose over emotional impact

Bloggers chase viral moments instead of solving reader problems

Nonfiction authors focus on sounding authoritative instead of being useful

Poets prioritize experimental form over human connection

The paradox: when you stop trying to be remembered and start trying to be helpful, readers remember you.

King didn't deliver that speech thinking "This will be my legacy." He delivered it thinking "These people are exhausted and need hope." The legacy came because the service was real.

Your reader doesn't need another impressive author. They need someone who understands their struggle and offers genuine help.

Service isn't a marketing strategy—it's a moral commitment. And it's the only path to work that outlives you.

Action Steps

Here's how to apply the MLK Framework and transform your writing from performance to service:

Interview your readers. Ask them directly: "What's your biggest struggle with [your topic]?" Write down exact phrases they use. Service starts with listening.

Audit your last three pieces. For each paragraph, ask: "Does this serve my reader or my ego?" Highlight anything that exists to make you look smart. Cut it.

Reframe every title as a solution. Performance title: "Reflections on Creative Identity." Service title: "How to Find Your Creative Voice When You Feel Lost."

Include one concrete action per piece. King didn't just inspire—he mobilized. Every article should give readers something specific to do immediately.

Test for clarity, not cleverness. Show your draft to someone unfamiliar with your topic. If they don't understand it immediately, you're performing instead of serving.

Track transformation, not traffic. Measure success by reader testimonials ("This changed how I think"), not pageviews. Service creates depth; performance chases breadth.

Write to one specific person. Imagine a reader struggling with the exact problem you're solving. Write directly to them, not to "everyone."

Ask better questions before writing. Not "What do I want to say?" but "What does my reader need to hear that no one else is telling them?"

FAQs

Q1: How do authors write to change lives instead of chase fame?

A1: By prioritizing reader transformation over personal recognition. Service-driven writing solves real problems, answers genuine questions, and offers practical help—measuring success by impact, not applause.

Q2: Doesn't focusing on service limit creative expression?

A2: No. King's speech was profoundly creative—but creativity served the message, not the messenger. Service provides direction; it doesn't eliminate artistry.

Q3: Can fiction be service-driven?

A3: Absolutely. Fiction serves by helping readers process emotion, understand human nature, or escape difficult realities. Service means respecting reader experience, not abandoning story.

Q4: How do I balance artistry with usefulness?

A4: Make artistry serve clarity, not obscure it. King used powerful metaphors and repetition—but to enhance understanding, not showcase skill.

Q5: What if serving readers means compromising my vision?

A5: Service doesn't mean pandering. It means ensuring your vision actually reaches and helps people instead of just satisfying your ego.

Q6: How do I know if my writing is truly helpful?

A6: Ask readers. Do they reference specific ways your work helped them? Do they recommend it to others facing similar struggles? Testimonials reveal service; likes reveal performance.

Q7: Can service-driven writing still be successful commercially?

A7: Yes—often more so. Readers pay for transformation, not performance. Books that genuinely help people sell through word-of-mouth for decades.

Q8: What's the biggest sign I'm writing for performance instead of service?

A8: If you're more worried about how you sound than whether readers understand and benefit. Performance obsesses over style; service obsesses over impact.

Call to Action

"Write to serve, not to shine. Learn how to create transformative work at BeyondTheBind.com/FreeTraining."

Sources

Stanford University – The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute

National Archives – "I Have a Dream" Speech Full Text and Context

Harvard Business Review – The Psychology of Service-Driven Leadership

Author: Curtiss Witt | Zzyzxx Media Group AI

Edition – Updated January 11, 2026