The Sweetener Discovered by Accident: How Do Authors Learn Through Failed Experiments?

How a forgotten dinner in 1879 proved that creative breakthroughs come from messy experimentation, not cautious perfection—and why your worst drafts teach more than your best ones

Definition

Learning through experimentation means treating every draft, project, and creative attempt as data collection rather than final performance. It's the practice of creating without attachment to immediate success, understanding that valuable discoveries emerge from patterns across multiple attempts—not from getting it right the first time. Experimentation replaces "Is this good enough?" with "What did I learn?"

Analogy Quote

"The breakthrough hides in the mess you were about to throw away." — CL Witt

Historical Story

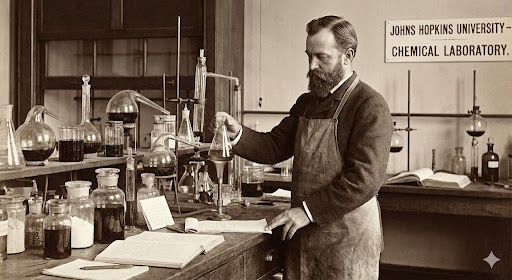

On a February evening in 1879, chemist Constantin Fahlberg sat down to dinner at his boarding house in Baltimore and bit into a roll.

It tasted impossibly sweet.

Confused, he ate another piece. Still sweet. He licked his fingers—sweet. He tasted his napkin—sweet. Everything he touched tasted like sugar, but there was no sugar on the table.

Then he realized: he'd forgotten to wash his hands after leaving the laboratory.

Earlier that day, Fahlberg had been experimenting with coal tar derivatives, trying to create new chemical compounds for an entirely different purpose. He'd spilled various solutions on his hands, made notes, moved between beakers, and never thought twice about the sticky residue coating his fingers.

That residue was saccharin—the world's first artificial sweetener.

Fahlberg wasn't trying to invent a sugar substitute. He was trying to understand the oxidation of certain chemical compounds. The discovery happened because he was willing to experiment without knowing exactly where it would lead.

He could have dismissed the sweet taste as contamination and scrubbed his hands. Instead, he got curious. The next day, he systematically tasted every compound he'd worked with the day before (dangerous, but this was 1879). He isolated the sweet substance, tested its properties, and within months had secured a patent.

Saccharin became a sensation—especially during World War I sugar shortages. Diabetics gained a safe alternative. Industries transformed. All because one scientist didn't wash his hands and didn't ignore an unexpected result.

The breakthrough didn't come from careful planning. It came from messy experimentation and the willingness to investigate failure.

Our Connection

Every writer has a "dirty hands" moment—a scene that won't work, a chapter that derails the plot, a draft so bad you want to delete it immediately. Most writers treat these failures as setbacks to overcome. But what if they're actually discoveries waiting to be investigated? Fahlberg could have dismissed that sweet taste. Instead, he got curious about the mess. Writers who breakthrough don't avoid failed experiments—they mine them for unexpected insights. Your worst draft might contain your best idea, hiding in the residue you were about to wash away.

Modern Explanation

The creative process has two modes: execution mode (trying to get it right) and experimentation mode (trying to learn something).

Most writers stay trapped in execution mode. Every draft must be good. Every sentence must sound professional. Every idea must work immediately. This mindset paralyzes creativity because it treats every attempt as a final judgment rather than a data point.

Experimentation mode asks different questions:

What happens if I try this structure?

What if this character did the opposite?

What if I removed this entire subplot?

What if I rewrote this scene from a different POV?

None of these questions demand success. They demand curiosity.

Fahlberg's discovery required three elements that all creative breakthroughs need:

Willingness to make a mess. He wasn't carefully protecting himself from contamination—he was fully engaged with multiple experiments simultaneously. Writers need the same freedom to try things that might not work.

Attention to unexpected results. The sweet taste was an accident, but recognizing it as significant required awareness. Writers must notice when something unplanned actually works better than the plan.

Investigation instead of dismissal. Fahlberg didn't ignore the anomaly—he studied it. Writers must examine failed experiments for hidden value instead of just moving on.

The irony: writers who chase perfection from draft one rarely achieve it. Writers who embrace experimentation often stumble into their best work by accident.

Breakthrough doesn't come from knowing where you're going—it comes from being curious about where the mess leads.

The Saccharin Framework

The Saccharin Framework teaches that creative development is iterative, not linear. You don't think your way to breakthrough—you experiment your way there.

Contrarian Insight

Most writers believe improvement comes from studying craft, reading writing guides, and practicing technique until they achieve mastery.

The truth: your biggest leaps come from productive failure, not incremental refinement.

Studying craft teaches you what's already been done. Experimentation teaches you what you uniquely can do.

Writers who obsess over perfection produce competent, predictable work. Writers who embrace experimentation produce surprising, original work—because they're willing to venture into territory where failure is likely.

Think about your favorite authors' breakthrough books. Were they refinements of what came before, or radical experiments that could have failed spectacularly?

Toni Morrison's Beloved experimented with non-linear narrative and magical realism

Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five broke every rule about plot structure

Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway experimented with stream-of-consciousness

None of these were safe choices. All were experiments that could have been disasters.

The paradox: the safer you play, the less distinctive your voice becomes. The more you experiment, the more you discover what makes your perspective unique.

Fahlberg wasn't a better chemist than his colleagues. He was more willing to work messy and investigate accidents.

Your failed experiments aren't wasted time—they're the laboratory where your distinctive voice emerges.

Action Steps

Here's how to apply the Saccharin Framework and learn through experimentation instead of perfectionism:

Give yourself experiment quotas. Before starting any project, commit to trying three things you've never attempted: new structure, different POV, unusual voice. Permission to fail enables discovery.

Keep a "residue journal." After every writing session, note what surprised you—unexpected phrases, characters doing unplanned things, scenes that went sideways. Review monthly for patterns.

Deliberately write "bad" drafts. Once a week, write something intentionally terrible—purple prose, cliché-heavy dialogue, melodrama. This removes perfectionism's stranglehold and sometimes reveals hidden gems.

Mine your rejected work. Return to abandoned drafts not to fix them, but to extract anything worth saving. What almost worked? What idea deserves a second life?

Try constraint experiments. Write a scene in 100 words. Rewrite it in 500. Then 50. Constraints force creative problem-solving and reveal new approaches.

Separate experiment from execution. Label some writing time "laboratory"—no judgment, pure exploration. Other time is "production"—polishing what you've discovered.

Share experiments with trusted readers. Ask not "Is this good?" but "What's interesting here?" Fresh eyes spot potential you might miss.

Track what you learn, not what you finish. After each experiment, write one sentence: "I learned that ___." Accumulate insights instead of only completed pieces.

FAQs

Q1: How do authors learn through failed experiments?

A1: By treating every draft as data collection rather than final judgment. Failed experiments reveal what doesn't work, what almost works, and what surprising elements deserve development—insights you can't get from playing safe.

Q2: Isn't experimentation just wasting time I could spend writing well?

A2: No. Experimentation is how you discover what "writing well" means for you specifically. Fahlberg didn't waste time with messy experiments—that's where the breakthrough lived.

Q3: How do I know which experiments are worth pursuing?

A3: Notice your own curiosity. If an experiment keeps pulling your attention even after it "fails," investigate why. Your instincts are data.

Q4: What if my experiments are genuinely terrible?

A4: Most will be. That's not failure—it's elimination. Edison tested thousands of filaments before finding one that worked. Each "terrible" experiment narrows the field.

Q5: Can I experiment while working on a book deadline?

A5: Yes, but separate experiment time from production time. Use early mornings or designated days for play. Use focused blocks for executing what you've discovered.

Q6: How long should I experiment before committing to an approach?

A6: Until something pulls you forward with genuine excitement. Commitment comes from discovery, not from arbitrary deadlines.

Q7: What's the difference between experimentation and lack of discipline?

A7: Experimentation is intentional exploration with observation. Lack of discipline is unfocused wandering without learning. Keep notes on what you discover.

Q8: Should I show experimental writing to anyone?

A8: Only to trusted readers who understand it's exploratory. Don't seek validation—seek insight into what resonated unexpectedly.

Call to Action

"Make the mess. Mine the breakthrough. Learn experimental writing at BeyondTheBind.com/FreeTraining."

Sources

American Chemical Society – The Accidental Discovery of Saccharin

Smithsonian Magazine – How Forgotten Hands Led to Sweet Success

Harvard Business Review – Innovation Through Productive Failure

Author: Curtiss Witt | Zzyzxx Media Group AI

Edition – Updated January 11, 2026